Economic Sustainability in a Time of Impact and Regulation

Link to the original article in The European Business Review

By Laurits Bach Sørensen, October 12, 2022.

It is imperative that the world accelerate its green transition. New technologies and new business models are fundamental in order to reach net zero, and it is vital that the alternative investment community as a whole rally around these drivers and support technologies with the potential to change the world for the better. However, the technologies that are necessary to save the world need not only to be sustainable – they need to be economically sustainable as well. Laurits Bach Sørensen, co-founder and partner at Denmark-based private equity firm Nordic Alpha Partners, shares his investment philosophy.

With increasing turmoil and turbulence, important infrastructure and technology need to be able to withstand changes from all angles.

The investment philosophy of Nordic Alpha Partners is to identify and support industrial “cleantech” businesses that are sustainable and can either contribute to or accelerate a green transition. We believe that private equity firms have a responsibility that is far greater than the returns we create. The sourcing activities and the economic support, as well as the operational value creation that the alternative investment community provides, are vital for the global commercialisation of the green technologies of the future.

In 2021, McKinsey1 estimated that if Europe is to reach net zero emissions, it would require €28 trillion of investment over the coming 30 years. McKinsey also identified that half of the required capital outlay would not have positive investment cases. Following this logic, if just 1 per cent of the necessary investments became positive cases, it should free up €280 billion that the EU could spend on increased welfare or increased transitionary support.

Positive investment cases in this sense are long-term investments that will reduce the EU’s overall operation costs, which means long-term, economically sustainable investment cases that are not created in or dependent on a regulatory-generated market.

Economic sustainability is based on free market principles and free market terms. Any investment that is a product of government regulation or situated within an artificially created market cannot be called economically sustainable. In essence, economic sustainability is about survival. It is about creating something that can stand on its own, resilient to outside influences and various dynamics of changing environments. It is an important distinction and nuance to the debate around impact versus sustainability.

The sustainable-investment sweet spot

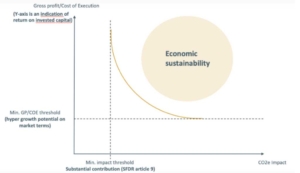

Nordic Alpha Partners uses this thesis of economic sustainability to find a sweet spot between sustainable impact and growth potential, which is essentially driven by a ratio of return on invested capital (ROIC). This is an example of our model using economic sustainability as an indicator of when and where to invest:

Along the Y-axis is an indication of the ratio between gross profits and cost of execution in a set investment, essentially the return on invested capital. The higher the gross profit contribution from commercial expansion and growth investments, the faster and more effectively we can scale the companies. Along the X-axis we identify a threshold of hyper-growth potential on free market terms, correlated with an impact threshold along the Y-axis and a CO2 impact counter along the X-axis.

This model provides Nordic Alpha Partners with an efficient way of qualifying new investment leads and checking whether they show a) sufficient return, b) sufficient growth potential on free market terms, and c) how this potentially carries impact.

Focusing on assets where we can achieve the highest gross profit over cost of execution on free market terms delivers the most effective results – an approach that has led Nordic Alpha Partners to make nine investments, eight of which fully qualify as SFDR article 9 compliant investments, according to an external ESG analysis by Klinkby Enge2.

Furthermore, the list of companies in NAP’s portfolio has already relieved the world 735,000 tons of CO2e (CO2equivalents3). By 2026, NAP’s portfolio of companies will relieve the world 2.5 million tons of CO2e every year, which is roughly 10 per cent of Denmark’s carbon footprint.

Without diligently supporting winning technologies, many brilliant ideas will fail and the ultimate goal of a fully sustainable world will remain out of reach.

The alternative investment community has a central role to play if the world is to reach its goals related to the green energy transition. Private equity firms, whether at the seed or buyout stages, are all experts in scaling transformative technologies. Almost every transformative technology company making a difference in the last three decades has been backed by private equity, largely because of the agility, insight, risk profile, and strength that private equity can provide in an environment operating on free market terms.

Without diligently supporting winning technologies, many brilliant ideas will fail and the ultimate goal of a fully sustainable world will remain out of reach.

The further philosophy of Nordic Alpha Partners is that the naturally occurring resources on our planet are sufficient to maintain economic growth and prosperity and sustain the creation of wealth in a way that can be distributed equally, in perpetuity. However, this level of sustainability is only achievable via an advanced technology transition. Without diligently supporting winning technologies, many brilliant ideas will fail and the ultimate goal of a fully sustainable world will remain out of reach.

How to spot economically sustainable transformative technologies

Succeeding on free market terms means that a company, a product, or an offering must be better, cheaper, simpler, and available (BCSA). If a technology or solution is all four of these things, it will most likely become a transformational leader while delivering high ROIC. I developed the BCSA method of thinking when I was CEO and chairman of a transformative greentech business called Microshade, as I wanted to understand what drove hyper-transformational technology adoption and returns. Today, the BCSA principle is one of the core drivers of NAP’s investment and growth strategy.

Where conventional solutions only need to be better and cheaper to dominate an industry, the green transformation is a technology transformation, which means that it relies on new solutions being adopted to substitute conventional solutions. These solutions are transformative by nature, and that is why conventional business school theory is not sufficient. For a new solution to be adopted, it needs to also be simpler or equally simple to adopt for customers or the market, and available in the right volumes, geographies, or services as the conventional technologies it is trying to substitute.

Many fantastic technologies never become a success despite being both better and cheaper than conventional solutions, because of the complexity of adoption and lack of large-scale availability, a reality that is especially problematic for greentech, as this is typically complex “hardtech”.

Sometimes even, green technology solutions are only better because they are “green”, but highly reliant on regulatory influence, making them cheaper and simpler than other alternatives.

The B and the C represent the standard business case, but the S and the A represent the ease of adoption. If an offering or a technology is all four of these things relative to its competition, there is no need for regulation or subsidies.

In comparison, within a heavily regulated or subsidised market, one very often finds that offerings are not BCSA on free market terms, and so would not be able to compete when subsidies disappear, or outside these artificial, generated markets.

An example from NAP’s portfolio is Re-Match, a listed company in Denmark that specialises in the recycling of decommissioned sports turf. Artificial turf is becoming increasingly popular globally, with tens of thousands of soccer fields being installed each year, allowing sports to be played everywhere, regardless of climate and maintenance. However, artificial turf has a lifespan of 8-12 years5, which means that, 10 years from now, the thousands of soccer fields installed will have become millions of tons of waste and, until recently, the only way of dealing with the exhausted turf was to dispose of it through either incineration or landfills, with a detrimental effect on the environment. Last year, 42,000 artificial sports turfs were installed globally6, which will produce an estimated waste stream of 11 million tons of waste in 10 years, equivalent to 60 billion plastic bags and with a negative environmental impact of around 18 million tons CO2e if incinerated7.

If decommissioned sports turf is instead sent to a Re-Match factory, the polymer fibres as well as raw materials from the infill, such as rubber and sand, can be recycled into new turf or substitute virgin material within production, saving the atmosphere millions of tons of CO2 emissions.

By setting up Re-Match factories in close proximity to large groups of artificial turf areas and providing a one-stop-shop recycling offering, priced cheaper compared to more polluting alternatives such as incineration or landfill, Re-Match is a great example of a green technology that is better, cheaper, and simpler, with only risk capital preventing it from becoming available, hence able to compete on free market terms and achieve high growth with the right level of investment.

The BCSA method is a quick and efficient way to check whether a technology has the potential to be economically sustainable and, thereby, a potentially vital player in the green economy.

Regulation can create artificial and non-viable market environments

It is natural to assume that governments should help spur these developments and provide incentives to industries, technologies, and companies that work with this kind of technology. And it is also true that a lack of regulation in the past has let the free market run wild in directions that were not in our planet’s best interest.

But, before we embark on a regulatory path, or start favouring one type of technology, we have to be aware of its potential effect on the market environment. While regulation is good in many instances of socioeconomic policy, in this case they may end up limiting the transitionary potential of new technologies.

A related issue is that politically created incentives often create a prolonged socioeconomic J-curve based on companies in the long run transitioning on to free market terms. This transition could have very long timelines and any projections on eventual returns would be subject to varying degrees of uncertainty. From my own experience, the longer the downward trajectory of the curve, the bigger the likelihood of other, more sustainable technologies being disadvantaged or even blocked by artificially created environments. There is also a risk that the J-curve becomes so prolonged that other technologies8 catch up, making the regulatory efforts wasted.

A timely example of this could be wind power, in the shape of the wind-powered turbine. It has taken decades of subsidies and decades of government-funded research and projects to bring wind power to par with other technologies. Who knows what alternative innovations and technologies might have flourished if that market had not been so powerfully supported? If Denmark had not created this market for wind power and the development of the wind-powered turbine, the industry would have looked very different today.

However, if incentives are to be used as a way of stemming the problems associated with rising carbon dioxide levels, CO2 tariffs are a better mechanism than specific technology subsidies in my opinion. CO2 tariffs do not favour certain methods and thus do not hinder competition or the competitive technology market, though we should be aware that such tariffs will drive suboptimal investment and business behaviour, as some companies will favour their EU presence and investments, despite being globally economically sustainable, and we will see technologies evolve based on this that will never become economically sustainable.

Collectively, it is a very difficult calculation and, without heavy regulatory influence, it is very unlikely that we successfully achieve net zero, but the closer one can get to the free-market principles driving the green transition, the easier the problems and challenges will be to manage and control, and the more cost-efficient the transition can become.

The key thing is to find the right balance between regulation and economic sustainability on free market terms, and to let that added context enter into the discussion at a high level.

Nuances are necessary

While there is not one defined solution to the challenges that we face in terms of backing the right businesses to create economically sustainable technologies and drive necessary impact, it is imperative that we add colour and nuance to the debate about how the alternative investment community can best support new technology.

The key thing is to find the right balance between regulation and economic sustainability on free market terms, and to let that added context enter into the discussion at a high level.

A solution could be to channel the efficiencies of the free market, as proposed above, making sure we become aware of the BCSA principles, and use them toward investing in the green transition in a more informed way.

It is this nuance that is lacking in the current debate, and if we do not consider the perspectives mentioned above, we risk having an inefficient economic transition that will affect our socioeconomic outlook and our prosperity overall in a very negative way.

I have identified three initiatives that the investing community in Europe and abroad can take to heart:

- We should be prioritising and financially fuelling green businesses and technologies that can sustain themselves outside artificially created markets and which are efficient on a global scale. This can be through a lens of economic sustainability as laid out, by using the BCSA logic.

- We should clearly quantify the societal and the environmental effects of various solutions and technologies so that we may prioritise the best business cases for society and be aware of the associated J-curves connected to various solutions. And if we politically see the need to prioritise specific technologies through regulation, we should set up dedicated regions and innovation hubs for the specific technologies, as Denmark has achieved around the windmill turbine industry, to ensure shorter, controlled J-curves and a conscious elimination of economically sustainable innovation and free market drivers within that region.

- We should develop and continue to build on models, methodologies and a language to ensure that we can contextualise the impact of CO2 against the societal cost in the debate on our society and our investment models. NAP GP/CoE(ROIC) vs CO2 impact could be the foundation for a micro-economic model.

About the Author

Laurits Bach Sørensen is the co-founder and partner of private equity fund Nordic Alpha Partners. He previously held executive positions at HP EMEA, as well as being CEO of Aastra Telecom Denmark and CEO and chairman of greentech business MicroShade. He has led exits from Ipvision and Optiware. He currently sits on the board of four cleantech companies: Re-Match, AquaGreen, DyeMansion, and Spirii. Overall, he has over 20 years of experience spearheading venture businesses, value creation, exits, and IPOs. He holds an MSc in Management of Innovation & Business Development from Copenhagen Business School.

Laurits Bach Sørensen is the co-founder and partner of private equity fund Nordic Alpha Partners. He previously held executive positions at HP EMEA, as well as being CEO of Aastra Telecom Denmark and CEO and chairman of greentech business MicroShade. He has led exits from Ipvision and Optiware. He currently sits on the board of four cleantech companies: Re-Match, AquaGreen, DyeMansion, and Spirii. Overall, he has over 20 years of experience spearheading venture businesses, value creation, exits, and IPOs. He holds an MSc in Management of Innovation & Business Development from Copenhagen Business School.

References

- How the European Union could achieve net-zero emissions at net-zero cost”, 3 December 2020 – McKinsey

- Klinkby Enge is one of Denmark’s largest ESG assessment consultancies. More information can be found at https://napartners.dk/esg/

- https://ecometrica.com/assets/GHGs-CO2-CO2e-and-Carbon-What-Do-These-Mean-v2.1.pdf

- As of 2021, Denmark’s CO2 footprint was 28.1 million tons. Statista, 27 July 2022.

- https://re-match.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Prospectus-for-Re-Match-Holding_Final_03.12.2021.pdf

- https://www.ami.international/cons/prod.aspx?catalog=Consulting&product=m290 – This figure is derived from the amount of turf material produced each year as indicated by AMI in their latest market report, divided by the size of the average turf field. For more details, see page 7 of the Re-Match IPO deck.

- Emissions from the incineration of the old materials and the production of new materials (one soccer pitch = 417.8CO2e) (Universal Textile Technologies, 2013, Life Cycle Assessment – Synthetic Turf Construction, Installation, and Removal).

- https://winddenmark.dk/sites/windpower.org/files/media/document/Profile_of_the_Danish_Wind_Industry.pdf

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!